But another argument, advanced by Richard Duncan, chief economist at Blackhorse Asset Management, who is based in Bangkok and a keynote speaker at April’s 18th annual Global Investment Conference suggests that events in the 1960s laid the foundations for recurring bubbles and busts.

The starting point is the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1968. Bretton Woods, while not a gold standard in the usual sense, had succeeded in curbing curbing trade imbalances between countries. When the U.S. renounced convertibility of the dollar into gold in 1971, “the dollar standard” came to govern the global balance of trade.

One result has been a persistent U.S. trade deficit with the rest of the world. With trade deficits come bubbles, in both the debtor country and the creditor country. Globalization has only served to encourage this, Duncan argues, “because of the extreme wage-rate differentials between the United States and the developing world, which inevitably lead to larger and larger trade imbalances and these trade imbalances have destabilized the global economy, firstly because the countries with the trade surpluses tend to blow into bubbles — Japan in the 1980s and the Asia-crisis countries in the 1990s.” Now it’s China as it recycles export earnings into whatever U.S. investments are available – and for the period from 1996 to 2006, there was a shortage of U.S. government debt to buy. So the money went into bubbles: in the U.S. because the money had to be invested; at home because the People’s Bank of China had to print yuan to buy exporters U.S. earnings.

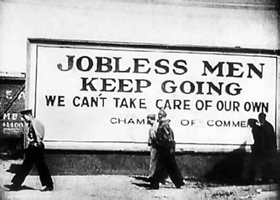

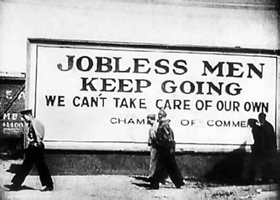

But there’s no going back to a self-regulating gold standard, Duncan also argues. That genie has escaped from the bottle and no amount of austerity will shove it back in. Says Duncan: “We could do what the Tea Party wants in America and immediately balance the government budget and ban the Fed. That would immediately result in us collapsing into a new Great Depression.” The world economy is far too dependent on credit-led expansion.

The second alternative isn’t much better. Indeed, it’s also a deflationary trap. “We could do what Japan has done for the past 23 years, continue to have very large budget deficits every year and stimulate the economy and keep it from collapsing into a depression that way, but just to spend all the money wastefully as Japan has done, building bridges to nowhere and paving the Japanese countryside with cement. That’s effectively what we’re doing now. We have very large budget deficits but we’ve largely been wasting most of this money on too much consumption and war. So we can do that for another 10 years, maybe and then eventually go bankrupt like Greece. That’s the most likely scenario.” Just treading water with expanded credit creation won’t do the trick.

Duncan’s preferred solution “is to learn from Japan’s mistakes and to understand that we’re going to have to spend this money to keep the economy from collapsing. But rather than spending it wastefully, the government should invest this money very aggressively on a very large scale in transformative 21st century industries and technologies. If they do, they could generate such a massive investment return that the returns would pay for the investments many times over. It would allow a complete restructuring of the U.S. economy that would the United States an absolutely unassailable lead in 21st century industries.”

It’s a unique moment, he argues, use cheap credit to something productive.