Thus James Hamilton, a professor of economics at teh University of Calfornia San Diego, and co-author of the Econbrowser blog, notes that “Some people think of the Great Depression as beginning or even caused by a stock market crash in October 1929. But Robert Shiller’s data indicate a broad market decline that month of 26%, not a whole lot worse than the 20% decline we saw in September 2008. From September 1929 to March 1931, the total stock market decline was 44%, which was milder than the 49% decline from September 2007 to March 2009. The Federal Reserve Board’s index of industrial production fell 28% from September 1929 to March 1931, somewhat more severe than the 17% drop recorded in the most recent recession. But if the U.S. economy had turned around in early 1931, we would be talking about that period as just another bad recession. The reason we instead call it the Great Depression is that the stock market went on to fall an additional 61% and industrial production an additional 27% from the levels of March of 1931.”

So where did the Great Depression come from? “Dramatic events in Europe included failure of Credit-Anstalt, Austria’s biggest bank, in May of 1931. That was followed by bank runs in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Poland, and Germany. As is often the case historically, the financial problems were a combination of a banking crisis– I’m not sure the bank will give me back my marks– and a currency crisis– I’m not sure that, if I get my marks out of the account, they will still be worth as much. I’d rather have gold than marks in an account with some shaky German bank.”

Yet, this was the era of the gold standard, that was supposed to impose discipline on debtor nations, who faced outflows of gold if inflation got out of hand. Famously, Winston Churchill, as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1925, put Britain back on the gold standard, fomenting the General Strike as workers faced real wage cuts to maintain an overvalued pound. That was the subject of a blistering attack by John Maynard Keynes, in his “The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill,” which was not an attack on the gold standard itself, but on Churchill’s implementation.

This is roughly the situation where the peripheral countries of Europe now stand: real wages that are too high for a euro standard which overvalues local goods and services.

Argues Hamilton: “In 1931, countries faced doubts about whether they would stay on the gold standard, and had a choice of either to abandon gold or else to inflict further domestic economic damage in the form of monetary contraction and price deflation. … In 2012, countries face doubts about whether they will remain in the European monetary union, and have a choice of either to abandon (or be forced out of) the euro or else to inflict further domestic economic damage in the form of more fiscal contraction. We’re watching those fears and their consequences today move from country to country in real time.

On the Great Depression front, economists Barry Eichengreen and J. Bradford DeLong also note the similarities between 1931 and today, in their preface to a reissue of Charles Kindleberger’s The World in Depression.

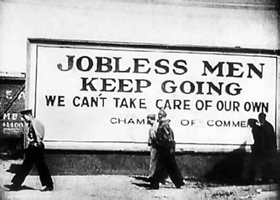

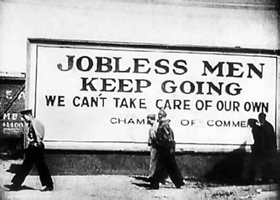

“The parallels between Europe in the 1930s and Europe today are stark, striking, and increasingly frightening. We see unemployment, youth unemployment especially, soaring to unprecedented heights. Financial instability and distress are widespread. There is growing political support for extremist parties of the far left and right,” they noted

“While much of the earlier literature, often authored by Americans, focused on the Great Depression in the US, Kindleberger emphasised that the Depression had a prominent international and, in particular, European dimension. It was in Europe where many of the Depression’s worst effects, political as well as economic, played out. And it was in Europe where the absence of a public policy authority at the level of the continent and the inability of any individual national government or central bank to exercise adequate leadership had the most calamitous economic and financial effects.”

For them, Kindleberger highlighted three features. “First, panic. Kindleberger argued that panic, defined as sudden overwhelming fear giving rise to extreme behaviour on the part of the affected, is intrinsic in the operation of financial markets. … Kindleberger was an early apostate from the efficient-markets school of thought that markets not just get it right but also that they are intrinsically stable.”

With panic comes contagion. “The 1931 crisis began, as Kindleberger observes, in a relatively minor European financial centre, Vienna, but when left untreated leapfrogged first to Berlin and then, with even graver consequences, to London and New York. This is the 20th century’s most dramatic reminder of quickly how financial crises can metastasise almost instantaneously. In 1931 they spread through a number of different channels. German banks held deposits in Vienna. Merchant banks in London had extended credits to German banks and firms to help finance the country’s foreign trade. In addition to financial links, there were psychological links: as soon as a big bank went down in Vienna, investors, having no way to know for sure, began to fear that similar problems might be lurking in the banking systems of other European countries and the US.”

Here they note that Greece is in the same position now as Austria was then. On the third point, the need for leadership, they quote Kindelberger himself:

“The 1929 depression was so wide, so deep and so long because the international economic system was rendered unstable by British inability and United States unwillingness to assume responsibility for stabilising it in three particulars: (a) maintaining a relatively open market for distress goods; (b) providing counter-cyclical long-term lending; and (c) discounting in crisis…. The world economic system was unstable unless some country stabilised it, as Britain had done in the nineteenth century and up to 1913. In 1929, the British couldn’t and the United States wouldn’t. When every country turned to protect its national private interest, the world public interest went down the drain, and with it the private interests of all… “