Despite an expected rise in U.S. interest rates, obscure or dangerous frontier markets can be a good way to get extra bond yields

Mongolia

This former Soviet country of less than three million people — some of whom still live as nomads in portable tents — likely isn’t top of mind for Canadian institutional investors. But it should be, some money managers argue: as a capital markets newbie, Mongolia offers attractive bond returns and economic growth fueled by untapped natural resources.

“The wonderful thing that happens when you first issue a bond is that investors suddenly discover you exist,” says Jan Dehn, Britain-based head of research at Ashmore, an emerging markets asset manager.

Mongolia issued its first bond in 2012. It has a junk-status rating of B — in line with other frontier countries, whose ratings tend to range from B- to BB. Of the $1.5-billion bond issue, $1 billion matures in 2022, with a yield of about seven per cent. The rest matures in 2018, with a yield of about six per cent.

This June, the government completed the sale of another $1 billion in bonds denominated in Chinese renminbi, making it the second nation after Britain to issue dim sum bonds.

Read: High correlation between Canadian, emerging markets

Choosing renminbi would bring Mongolia a lower interest rate, says Nicholas Hardingham, a Britain-based portfolio manager with Franklin Templeton’s emerging markets debt group. “If they were to go to the dollar market, they would be forced to pay something similar to what they’ve got on the outstanding 2018s and 2022s.”

About 93 per cent of the bond went to Asian buyers; Europeans snatched up the rest.

The state-owned Development Bank of Mongolia has also issued $580 million in bonds. These sovereign notes mature in 2017 and yield about six per cent. In May, the bank said it’s planning another bond issue of $1 billion.

“One big mine”

What makes Mongolian debt appealing is the country’s vast natural resources, including copper, gold and coal. Many of these resources remain untapped. “Mongolia is just one big mine,” Dehn explains. “There’s very little else going on in that country.”

In June, the government struck a deal with mining company Rio Tinto to expand operations in the Oyu Tolgoi mine, home to one of the world’s largest copper-gold deposits. It’s believed to have 81 billion pounds of copper and 46 million ounces of gold. The deal came after a two-year dispute with Rio because the government wanted more favourable terms.

“One can call it resource nationalism,” says Rajeev DeMello, Singaporebased head of Asian fixed income at Schroders. “The signing of this deal reflected a change in the attitude of the government.”

Read: Investors pouring back into Asia

DeMello expects the Rio deal to unlock other mining projects in Mongolia, such as Tavan Tolgoi, the world’s biggest untapped coal mine, believed to contain 6.4 billion tons.

Not for everyone

But for all its promise, the Central Asian country isn’t risk-free. And it’s not for everyone. “It’s for very sophisticated investors— for institutions that take a longer-term view and can build a highly diversified portfolio,” DeMello says.

The biggest threat is the economy’s overreliance on mining, which makes it vulnerable to commodity cycles, explains Alisher Ali, Myanmar-based chair at Silk Road Finance, an investment firm focusing on frontier markets.

Read: Global investment trends: Here be dragons

For example, Mongolia’s recent dispute with Rio Tinto caused existing mining deals to collapse, which coincided with a decline in global commodity prices. As a result, economic growth slowed to seven per cent in the first nine months of 2014, compared with more than 12 per cent during the previous year.

Also, more than 90 per cent of Mongolia’s exports go to China. So, if the Chinese economy continues to cool down and its need for raw materials declines, Mongolia will suffer, says Ali.

Political risks lurk, too. Mongolia has only been a democracy since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, so institutional weaknesses and breakdowns in the political process are common, cautions Hardingham.

Nobody will blame you if you think Iraq is a dangerous place to put your money. Well, almost nobody. Where many investors see brutal violence and a contracting state-run economy, some asset managers see opportunities, pointing to the country’s foreign exchange reserves and higher oil production.

“This is a classic example of a country where you have very high headline risks due to the security situation [and] instability within the government,” says Kevin Daly, a Britain-based emerging market debt portfolio manager at Aberdeen Asset Management.

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which grew out of al-Qaeda in Iraq, controls territories in the western and northern parts of the country. The Iraqi military has been fighting the jihadists since early 2015.

Read: Four emerging markets investment trends

However, investors are “more than compensated” for the ISIS risk, given that Iraqi sovereign bonds return around eight per cent, says Nicolas Jaquier, British-based emerging markets economist at Standard Life Investments. “It’s one of the highest-yielding bonds in our universe, apart from some countries that are close to default or in default, [such as] Argentina or Venezuela.”

Rating agencies haven’t rated the bonds, which contributes to investors’ skepticism. Aberdeen’s own rating of the bond is B+, in line with ratings of frontier countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, Daly notes.

Denominated in U.S. dollars, these bonds are Iraq’s first-ever issue, totalling $2.7 billion. That 2006 issue was part of an effort to restructure the debt accumulated under Saddam Hussein, Jaquier explains. The bond matures in 2028.

In April, the government said it’s planning a new international bond issue of $5 billion. That issue won’t come in one tranche because issuers rarely ask for more than $2 billion at a time, Jaquier explains. “Especially in the case of Iraq, since they haven’t come to the market in many years, it would be surprising if they did the $5 billion. What’s expected is $5 billion over the next few years.”

In June, the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region also announced it may issue bonds for the first time if there’s investor demand.

Why buy?

One reason Iraq’s bonds are a good investment is the country’s relatively low debt-to-GDP ratio: around 37 per cent. Also, Iraq has about $74 billion in its foreign exchange and gold reserves. “[That] makes us confident that they have the resources to pay their debt,” says Jaquier.

And Iraq is one of the few oil-exporting countries that has increased oil production despite sliding crude prices. A year ago, it produced about three million barrels a day; now it puts out 3.8 million barrels a day. Daly says increased production is good for Iraq because prices will hopefully rebound. Even if they don’t, high production can offset some of the shocks resulting from declining prices.

Read: Money managers worry about emerging markets

The oil sector provides more than 90 per cent of Iraq’s state revenue and 80 per cent of its foreign exchange earnings. So declining crude prices have hurt the economy: after growing by four per cent in 2013, it shrank by 0.5 per cent in 2014.

“Ultimately, these guys are going to get hurt — and so will the other big oil exporters” when more Iranian oil comes on the market, Daly says. Iran now exports around 1.5 million barrels daily. But it’s expected to boost exports in the foreseeable future, now that Tehran and the West have agreed to lift Iranian sanctions in exchange for the Islamic Republic limiting its nuclear program and providing guarantees of its peacefulness.

Another glimmer of hope is the slight improvement in Iraqi politics, Daly notes. Under Nouri al-Maliki, who served as prime minister from 2006 to 2014, sectarian divisions gridlocked the government. Al-Maliki concentrated power in the hands of his Shia allies, alienating the country’s Kurdish and Sunni minorities.

“Al-Maliki was seen as an impediment to development — to addressing issues like the oil sector and security,” explains Daly. Foreign investors see the new prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, as more inclusive.

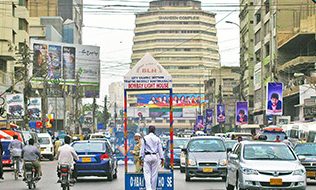

Pakistan

Taliban insurgents gunning down children. Flare-ups in the ongoing conflict with India over the sovereignty of Kashmir, the world’s biggest and most militarized disputed territory. And, most recently, a heat wave claiming hundreds of lives. The news from Pakistan is usually depressing.

But some argue investors need to focus on the country’s improving macroeconomic indicators, which make its bonds attractive despite the government’s debt default in 1999.

“It’s been a risky country, and its bonds were really shunned by global investors until the current government took over and started implementing some IMF [International Monetary Fund] recommendations,” says DeMello. “Since then, the tide has turned.”

Read: Chinese stocks continue falling

In 2013, Pakistan embarked on a 36-month IMF program. To get quarterly loan disbursements, the government has to meet certain economic criteria. “Pakistan has been doing quite well under that program, implementing structural reforms,” says Jaquier, adding the program has restored investor confidence.

The country has boosted its foreign exchange reserves to $18.2 billion and improved tax collection, notes DeMello. And it has kept its public debt manageable, at 64 per cent of GDP in 2014. But growth has been on the lower side by frontier market standards: just four per cent in 2015.

Besides IMF cash, as an oil importer, Pakistan has benefited from low oil prices, notes Daly.

Pakistan’s latest bond issues are from last year. In April 2014, the government issued $2 billion in dollar-denominated securities. Half of the notes have five-year maturities, yielding about seven per cent, while the rest have 10-year maturities with a yield of about eight per cent. In December 2014, the government also issued five-year, dollar-denominated Islamic bonds totalling $1 billion, with a yield of about seven per cent. More bond issues are likely later this year, Jaquier says.

Deadliest Taliban attack

Despite Pakistan’s recent credit upgrade, its bonds still have a junk rating (B3). A major reason is the country’s struggle with jihadist insurgents.

“It’s [a] place where you have to be aware of the risks you’re taking. But things have improved since the end of last year,” says Jaquier. That’s when Pakistani Taliban militants attacked an army-run Peshawar school and killed 141 people — most of them children. It was the Taliban’s deadliest attack in Pakistan and a watershed moment in the country’s fight against the insurgents.

Read: ETFs headed for the frontier

“It really brought together all of the different political parties and factions in Pakistan,” says Jaquier. Before the massacre, unanimity on how to fight the Taliban was lacking, with some favouring negotiations instead.

Yet despite Pakistan’s increased resolve to fight extremism, results are slow to materialize. In May, 45 Ismaili Shia Muslims were gunned down on a bus. Members of the Pakistani Taliban and the Islamic State both claimed responsibility for the attack.

Yaldaz Sadakova is associate editor of Benefits Canada.

Get a PDF of this article.