While some may turn to governments for aid, central banks cannot absorb the full impact of private sector deleveraging. Private capital is also insufficient in size to meet deleveraging needs. Thus, economies have two basic choices, a default/restructuring, such as Greece, or enacting repressive monetary policy, such as quantitative easing in the U.S. While the outlook may seem bleak, in a capital-starved, deleveraging, and complex world the return potential from credit investments can be substantial.

To unlock value in this economic scenario, an investor needs patient capital, the ability to analyze relative value opportunities, and the ability to understand politics. An investor can pursue this goal via two paths, opportunistic/directional or relative value/market neutral strategies. The former requires patient capital and creates value through focusing on senior parts of the capital structure or becoming an active investor. The latter aims to exploit market dislocations that are a direct consequence of deleveraging and regulation.

Of the three major balance sheets available to investors—consumers, governments, and corporations—corporations are in the best shape. Corporations started with better initial conditions after the dot-com crash and have been better managed through the present crisis. For example within corporates, we prefer bank loans over high yield. Companies have cash flows tied to assets that are volatile and sensitive to changes in the macro environment. Loans are senior in the capital structure and have a priority claim to those cash flows, generally experiencing lower volatility and higher recovery. In our view, loans offer better volatility and loss-adjusted return in this “new normal” world.

Turning to relative value strategies, in order for investors to capitalize on opportunities they need to assess macro-economic and policy implications, understand the interconnectedness of the financial markets, and analyze relative valuations. For example, two seemingly independent asset classes, Greek sovereign risk and U.S. non-agency RMBS paper, turned out to be correlated after problems in Greece caused investors to fear that European financial institutions would sell their U.S. non-agency MBS positions. An additional area for relative value creation is within the financial sector, which remains extremely complicated and full of opportunities. Understanding credit losses on a bank’s mortgage portfolio is no longer sufficient. An investor must understand the origination of the loans, legal implications of various scenarios, and liability transfer at minimum. An investor who comprehends the bank’s assets can better understand where mispricing lie within the liabilities.

At a time when macro-economic and policy events dominate market movements, a prudent investor must be capable of understanding the complexities within the corporate credit universe. Despite low yields in the market, attractive opportunities are available within the relative value space and these do not require an investor to forecast where the market will be three months or a year from today. An investor who has resources to analyze the interconnectedness of the financial markets and has patient capital to deploy can capitalize on these opportunities despite the uncertain investment environment that surrounds us.

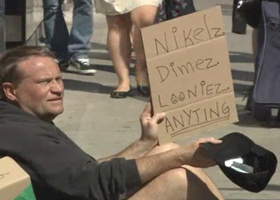

Rudy Pimentel is Executive vice-president, PIMCO.