When it comes to the difficult issue of equity in pension plans, Quebec has been at the forefront recently with its plan to table a bill to eliminate so-called disparity clauses.

The province’s plan, which has significant union support, has drawn the attention of Quebec’s pension industry, particularly since it would affect organizations that have set up two-tiered pension schemes by, for example, closing their defined benefit plans to new entrants and offering them defined contribution arrangements instead. The plan followed recommendations by a government-formed working group, which presented two options for eliminating such disparities: offer the same type of plan to all workers or an equivalent arrangement for everyone.

Read: Quebec employers concerned about province’s plan to eliminate pension disparities

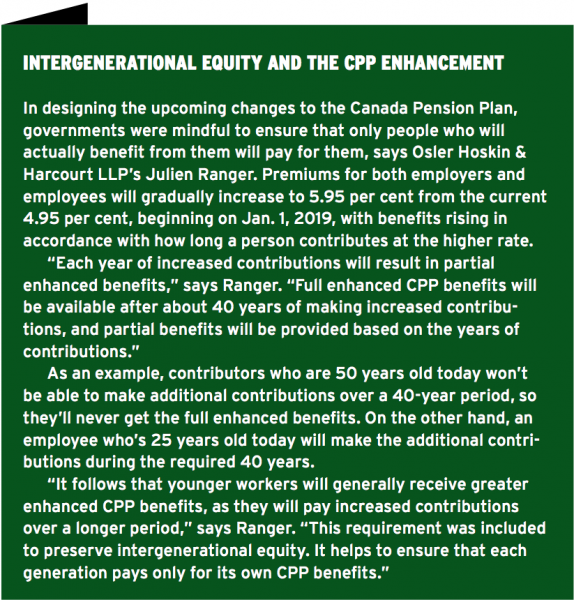

There are many of ways, of course, of looking at equity issues in pension plans. A frequent concern that comes up is intergenerational equity, an issue Julien Ranger, a partner at Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP in Montreal, notes is separate from the current Quebec discussions since a new employee could be any age. But when it comes to questions of intergenerational equity within a particular plan, plan sponsors do have a number of tools at their disposal to address the issue.

Adjusting inflation protection

Inflation protection is no longer an issue for British Columbia’s college, public service and teachers’ pension plans, according to executive officer Dominique Roelants, who notes they’ve managed inflation through a separate account since the 1980s.

“It was sort of a negotiated cost mechanism, so there was no guarantee. And what the boards inherited was what I would call cliff indexing, by which we pay out full indexing until we can’t do it anymore, and then we pay out whatever we can.”

So if inflation ran at six per cent for 20 years and drained the account, it would create intergenerational inequity between those who retired before and after, says Roelants. Recognizing the problem, the board changed its indexing policy, he notes. “And then we do as best we can from the funding available to provide inflation protection.”

Read: Ontario Teachers’ to partially restore inflation protection for newer retirees

Every three years, the plans’ actuary determines whether or not they can pay the same level of inflation protection in perpetuity. “Right now, the college pension plan won’t pay any more than 2.07 per cent inflation because, if it paid more than that, it would run out of money,” says Roelants, noting that would disadvantage younger members.

In the case of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, if it were to experience significant investment losses or a funding shortfall, it would bring itself into balance by either increasing contribution rates or reducing inflation protection, according to its 2016 annual report.

But as more teachers retire, there are fewer active members to fund major losses and it’s unlikely that increases to contribution rates alone would be sufficient, according to the report. And with any increases falling solely onto active members, the plan has added conditional inflation protection to its plan design for benefits earned after 2009 in order to spread the risks more broadly. Under the provision, inflationary increases for those benefits depend on the plan’s funded status, with the amount determined by its joint sponsors.

The potential unbalance between retirees and active members is the primary reason the plan provides conditional inflation protection, says Barbara Zvan, chief risk and strategy officer at the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and board chair of the International Centre for Pension Management.

Read: Governance, innovation touted as keys to Canadian pension funds’ success

“That active group can’t keep shouldering the burden. And now, we can split it between both generations — the generation that’s retired and the generation that’s working. That improves intergenerational equity.”

Zvan calls inflation protection the most popular way to manage intergenerational equity. “With any other benefit, you can’t change accrued benefits, and so you can only change go-forward benefits. And it’s not so easy to turn it on and off. With inflation, you can turn on and off. From a dollar point of view, it has substantial value.”

Changing contribution levels

Setting the right contribution rates for both the employer and employees is another way to ensure intergenerational equity, says Zvan. When Ontario Teachers’ plan members contributed eight per cent of their salary, the implied rate of return from their first contribution to their last pension cheque, as projected using demographic assumptions, was more than five per cent after inflation each year.

“Over the long term, we considered this a high target,” says Zvan. “When the members contributed about 11 per cent of their salary into the plan, the implied rate of return falls to about four per cent return, after inflation, each and every year. We considered a four per cent real return . . . as a more reasonable target over the long term, thus balancing intergenerational risk.”

But in some cases, a plan that’s raising contribution rates for active members could be inadvertently asking them to pay for the benefits of a generation that has already retired. For example, one of the amendments to Quebec’s municipal pension plans in 2014 required active members to contribute 50 per cent of the plan cost by Jan. 1, 2017. Considering what that means for intergenerational equity, Ranger notes a working police officer in Montreal is now getting a less generous deal than someone who retired five years ago. “You can play with benefits like that, but you have to be mindful or you’re going to create some sense of unfairness,” he says.

Read: Quebec introduces bill to reform municipal pension plans

When a plan sponsor is considering a change to contribution rates, it’s important to ensure the governance committee represents everybody’s best interests. However, with representation from the employer, employees and retirees, there’s bound to be a clash of opinions, says Robert Brown, a professor emeritus of statistical and actuarial science at the University of Waterloo.

“The retirees are obviously going to do everything they can to make sure the plan is absolutely fully funded. And those who are active in making the contributions will try to do the exact opposite, to find the lowest possible contribution rate that will allow them to get through the next valuation. I would rather have a model like Ontario Teachers’ where you have a board of trustees made up of experts. . . . Then, you don’t get into those same intergenerational, philosophical problems.”

Removing early retirement subsidies

Early retirement subsidies, which reward long-serving members while penalizing younger ones, also affect intergenerational equity, says Roelants.

In the 1970s, as school boards across the country hired a lot of young teachers, many provided so-called rules of 85 or 90 — providing for retirement eligibility when age plus years of service equal the number in question — which meant those who started working in their early 20s could retire in their mid-50s with an unreduced pension, notes Roelants. But that scenario is out of date as people entering the profession today often work as supply teachers for several years before landing a full-time job.

“So their ability to take advantage of some of these plan design features doesn’t exist,” says Roelants. “I mean, the average entry in the teachers’ plan is about 32 years old. You’re not going to get any advantage from a rule of 90 out of that. So a lot of those rules that used to exist, and still do in a lot of plans, are not really suited to the current work experience of the new members.

Read: Pension plans need new metrics to adapt to millennials’ ascent, changing work reality

“Plan sponsors have to bite the bullet and make the decision to change the plan design to make it fair for all generations. So the teachers’ and the college plan in B.C. have both done that, and hopefully more will follow suit.”

Indeed, the B.C. college plan now provides a flat rate reduced by three per cent per year if a member retires before age 65, says Roelants. Previously, members could receive an unreduced pension at age 60. The plan also included a bridging provision that would top them up to the full two per cent benefit when they turned 65.

By way of example, Roelants refers to a 30-year-old person and someone aged 35 who join the plan on the same day and both work for 30 years. “The one who retires at 60 would get five years of the full two per cent pension and then from 65 on would get the same pension that the other person got from 65. Contributing exactly the same to the plan, but one person gets five years more in value from it and five years more in value before even the normal retirement age.”

Two-tier pension plans

For employers considering a move to a two-tier pension plan and aiming to ensure intergenerational equity, a target-benefit arrangement is a better alternative than a defined contribution one, says Brown.

“I think you can get most of the advantages of a pooled-resources, pooled-asset defined benefit plan out of a target-benefit plan. Whereas if you go to individual accounts, they’re just awful. We have to find a way to keep expenses down in the accumulation period, and then we have to have a grouped approach to the longevity risk in the payout period.”

While many older employees are in defined contribution plans, it’s the younger members who will spend the majority of their careers in them, says Zvan. And while she sees target-benefit plans as a good option, she believes it’s a bit late in the game. “If you’re a private employer in a DC setup, are you really going to go down that route? I think, conceptually, it’s a great idea. [It’s] not very much different or a stretch from what we have at Teachers’ as a group.”

Read: Quebec smelter employees reject proposal for two-tiered pension plan

And when it comes to equity issues within defined contribution plans, Roelants notes they, too, have their complexities. While touted as being simpler in general, the outcomes in defined contribution plans will often turn on timing, which adds a wrinkle to the question of whether intergenerational equity issues arise. “On the whole, the answer should typically over the long run be no,” says Roelants when asked whether the generational issue is at play.

“But the weird thing is, for the last 25 years, the answer has sort of been yes. We had peak interest rates back in the early 1980s, and so people who were retiring out of DC plans in the 1980s and probably also in the 1990s probably did pretty well. Somebody paying exactly the same amount of money in who tried to retire in 2010 did pretty miserably.”

Roelants refers to numbers he has seen that showed income replacement levels ranging between 17 and 50 per cent at different times for members contributing the same amount and retiring after 25 years. “All that was just dependent on market timing,” he says.

“And so why I said typically the answer would be no for intergenerational equity is market timing. If you bought a whole bunch of stocks in early January and you sold them the second week of February, you lost a truckload of money. You shift that all over three weeks, you made a bunch of money. Ups and downs in the market, that’s just how it goes; that’s not intergenerational equity issues.”

Read: Canada to still lag behind OECD average replacement rate for typical workers: report

Ultimately, intergenerational equity is a loaded gun, says Serge Charbonneau, a partner in Morneau Shepell Ltd.’s pension consulting practice. He notes that even if two employees are both in a defined benefit plan, it may not treat them the same way. “If you’re 50 years old, the promise of $1 of pension at retirement is not worth the same as a 25-year-old, because one of them is very close to receiving it and the other is going to receive that same dollar but way down the road.”

It sounds good in principle to say a plan will treat all members the same, but it may look different in reality, he adds. “Is treating everybody the same giving them each $1 of pension at retirement or is it giving each person $1 into their DC account? At face value, those two statements sound as equitable as each other, but they’re not.”

Zvan expresses a similar sentiment, noting that while intergenerational equity sounds like a straightforward concept all pension plan sponsors should strive for, it’s difficult to measure in practice.

“You can always get a sense of whether you’re moving in the right direction, but there’s no expectation of, ‘Here’s the metric that we look at . . .,’” she says. “It also depends on how people want to run a plan.”

Jennifer Paterson is the managing editor of Benefits Canada.